There comes a point in any company’s growth when it introduces a major product and faces the question of whether to launch a new brand or keep it all under one roof.

Not every idea needs its own identity, but certain scenarios make it worthy of consideration. Perhaps a new product represents an expansion into a whole new category. Or a separate team is needed to focus on growing a unique area of the business in a certain market segment. These might be good reasons to introduce a new brand.

However, this isn’t a question to be taken lightly. A true “brand” is a difficult thing to cultivate in any meaningful way with your audience. It must represent something distinctive. It must maintain a cohesive message and presence, and deliver consistently on its promise across all touch points.

If you try to make one brand all things to all people… you risk muddling your message

If you try to make one brand all things to all people when you really should be separate brands, you risk muddling your message and diluting your brand. But, if you create multiple brands unnecessarily, you waste energy trying to maintain them and you lose opportunities to build brand equity and loyalty where it matters.

So how do you choose?

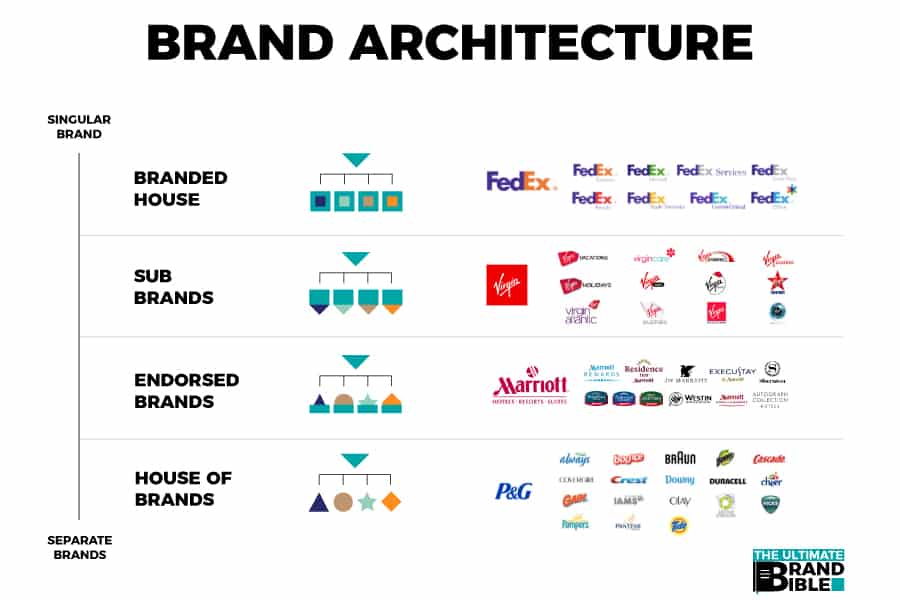

On the spectrum of options, brand strategists generally put the “branded house” model at one end and the “house of brands” model at the other. In the middle exists various hybrid arrangements to fit the unique needs of a given situation. But, to keep things simple, we’ll treat this as a choice between one extreme or the other.

There are two cases in which “house of brands” approach makes sense.

- The audience is fundamentally different

- The product needs to represent a different idea, ethos, or vibe

Case studies

Lexus is owned by Toyota. While the product lines may differ only in the details, Toyota understands that luxury car buyers share a set of characteristics that are quite different from those on the Toyota lot. Offering distinct brands not only serve to distinguish marketing and sales strategies, it helps to organize cultural values and thinking within the company. Designers and engineers on the luxury side will specialize in higher-end materials, more advanced technologies, and aesthetic excellence.

Where Toyota might be reaching different audiences, someone like Procter & Gamble serves potentially the same audience, but in very different ways. For example, they own both Folgers and Pampers. If you drink coffee and have very young children, P&G might be just your thing. But they also know that no one wants to think about diapers when sipping their morning joe.

The mental associations people build around a brand matter, and if there is any conflict… it’s a good sign there needs to be some distance.

One more example: Coca-Cola. There are over 500 brands owned by Coca-Cola. Not just a variety of soda flavors, but teas, juices, and water. All drinks, but very different flavor profiles. Why don’t you see the Coca-Cola logo stamped on these labels? Because that brand has a distinct meaning to consumers and the label needs to focus on the sub-brand the defines the experience they expect.

For each of these companies, a “house of brands” approach gives them further reach into a markets and opportunities they haven’t tapped into, and simply offering new products under the same brand would not be as effective. The mental associations people build around a brand matter, and if there is any conflict in the message, the marketing strategy, or the personality of the products, it’s a good sign there needs to be some distance.

Ask yourself these questions as you determine which approach is right for you:

- Are you trying to reach a new audience that would not be attracted to your existing brand?

- Are you trying to create a new experience that is substantively different from that which people expect from you today?

- Does your new product or service require a very different marketing strategy and message?

- If you altered your current brand, audience, and marketing strategy to reflect your expanding services, would your new message become too complicated and confusing, or would it actually make you even more appealing to an important segment of your audience?

A “yes” to the above questions indicates you may be better off introducing a new brand to the mix, so long as you’re prepared to do the work of maintaining it properly. And if you’ve gotten to this point because you believe the idea adds substantial value to your business, it’s probably worth its own weight.