When it comes to branding and logo design, timelessness is usually the Holy Grail. But, the reality is that we can’t all be Coca-Cola, Ford, or IBM.

Most companies go through several logo iterations and brand identities in their early years, and even established ones still need an update every 15-20 years as trends change.

Sometimes a rebrand is needed after a merger, or in the wake of a scandal, or just to signify that there is new leadership and an exciting new vision shaking things up. Whatever the reason, a fresh change of an organization’s visual branding can energize audiences and demand attention.

The trick, however, is getting it right. Because of the long lifecycle and omnipresence of a company’s logo, it carries tremendous responsibility. In that tiny little package lives a unique message about who you are, what you stand for, and what you promise. Anyone who has been through such a process understands how grueling (and surprisingly expensive) it can be.

A fresh change can energize audiences and demand attention.

Making the wrong call can lead to disastrous results. So, as a client working with an agency—presented with a multitude of branding options—how do you make the right decision? At a glance, there appear to be just three options:

- Go with your gut.

- Go with the agency’s recommendation.

- Ask for a vote from your customers or stakeholders.

There are problems with all of these, though. Your personal taste may not represent the taste of your brand’s audience, or you may be tempted to take the most safe (read: boring) route.

Your agency should have an informed, outside perspective, of course, and they’ve no doubt labored over a thousand questions to perfect their design. But, your agency isn’t your customer, and even the best agency would admit that they couldn’t possibly understand your business as well as you do.

Unfortunately, customer feedback isn’t all that helpful, either. Design isn’t democratic: the average person lacks the necessary professional experience and project context in order to make a strategic call.

The right solution is actually a mix of all three. Your agency should help you articulate what you think is needed, design a research plan to gain insights or confirmation from your audiences, and distill all of that into a compelling recommendation. We’ve seen this delicate but important mix succeed on a number of Polymath branding projects.

Data has a way of reducing the inherent subjectivity in the creative process.

To illustrate how this works in action, consider a rebrand Polymath did for an organization that has a national footprint and has been around for decades. We knew it was critical that stakeholders within the organization supported the outcome, so we designed a research plan that would give them an opportunity to weigh in upfront and also allow for testing the final options with the customer audience towards the end of the process.

When it came to the audience testing, we didn’t simply show a few logo options and ask what they like. That can produce all sorts of misleading results. Our plan went like this:

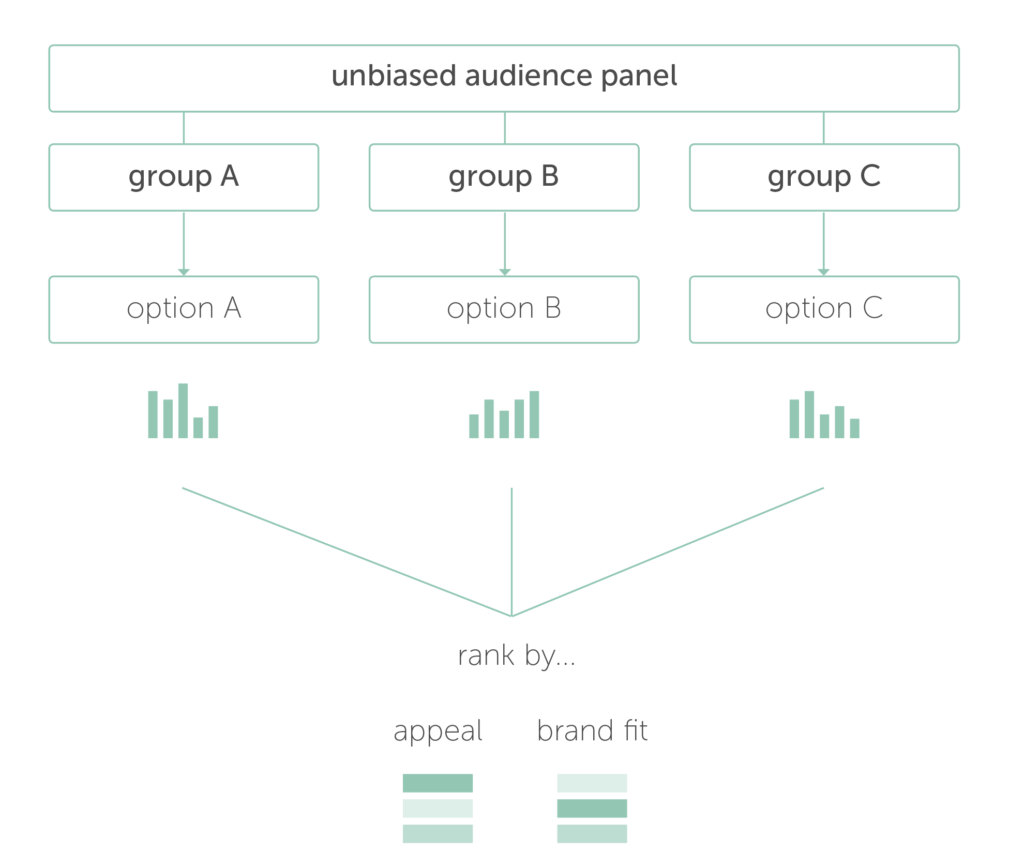

- We identified a large group of survey participants who matched the profile of our customers, but who had never heard of the brand, thereby eliminating familiarity biases. (For this particular client, it was essential that the rebrand help them shift their appeal to new audiences, not only to please their existing fans; hence, the focus on external surveys made most sense.)

- We split the survey audience into three groups who each saw a different variation of the branding. They were asked how it made them feel, what attributes it brought to mind, and how likely they would be to engage with this brand. (Removing comparisons between options also allowed for the truest customer feedback, as comparison often introduces a pressure that forces the brain into a less emotive mode of thinking.)

- Only after each group finished with their comments were they shown the other logo variations and asked to rank them in order of how closely the visuals represented the attributes we had previously defined that the new brand should convey.

- Participants were then asked to rank all options a second time, but in order of personal appeal. This was saved for last, so they wouldn’t simply champion their own, completely subjective favorite throughout the survey.

The results of this A/B test provided a more accurate picture of how new target audiences might respond in a real-world scenario. We could see that, when shown all options, the audience scored two of them about the same in terms of general appeal. But, when isolated, only one branding option clearly inspired a more positive response than the other. That data point was key in helping us—and the client—arrive at a decision.

The last step of our project was a pilot test of the new branding at two company events. This in-person feedback enabled us to move forward with a larger national rollout that will soon be seen by upwards of 100,000 people per year at live events across the U.S.

A lot of intuition and experience goes into a design project, yes, but, as we’ve shown, good data has a way of reducing the inherent subjectivity in the creative process. When you need to be confident in the results, or you need to win over the naysayers, a well-designed research and testing element can make all the difference.